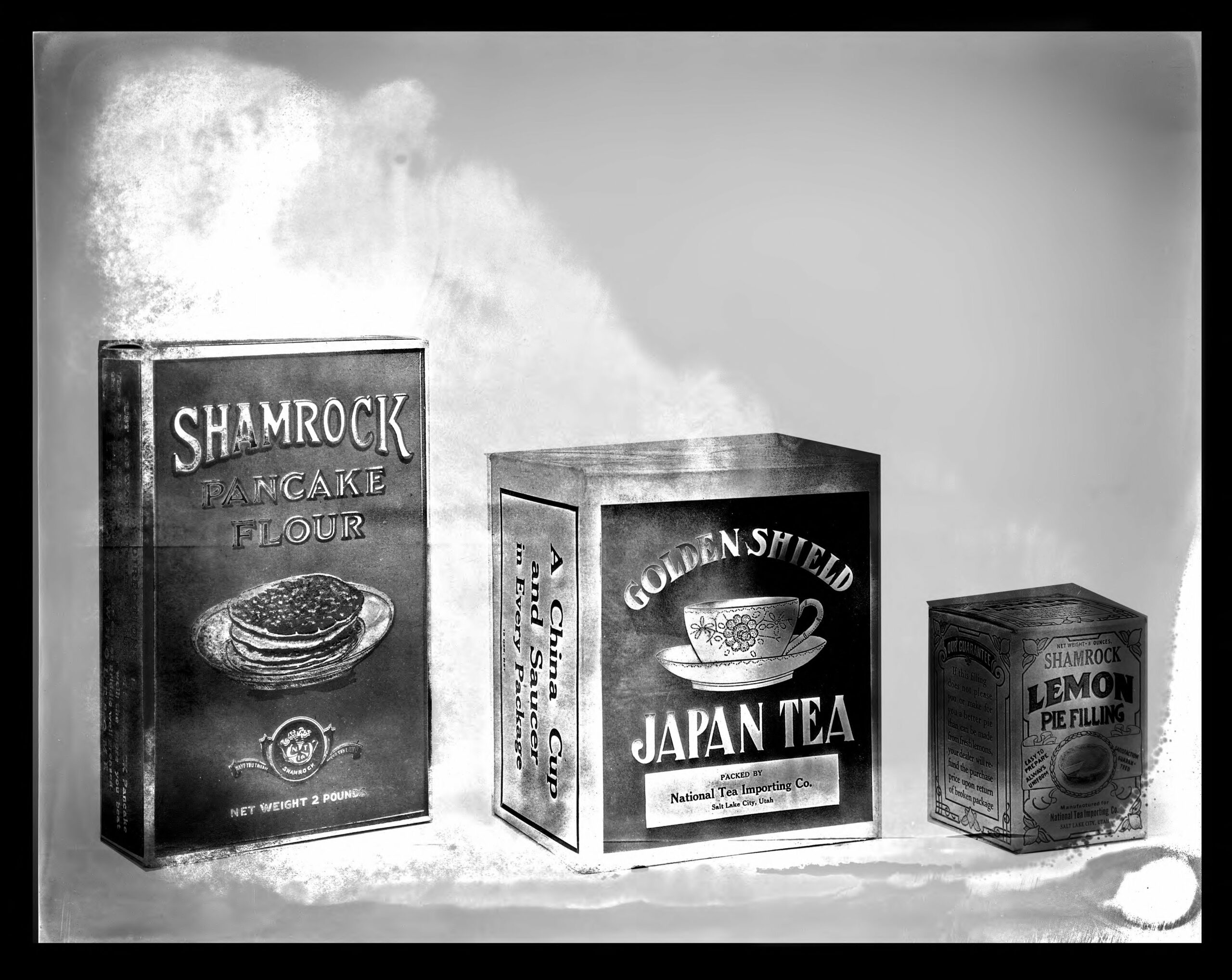

Featured image: National Tea Importing Co., Tea, by Harry Shipler (1920)

All teas come from the same plant, camellia sinensis, and the levels of oxidation and processing endured by the leaves determine their eventual identification as black, oolong, green, or white tea. When I worked at a loose-leaf tea store, I liked to tell people that drinking black tea was literally drinking a bruise, because producing black tea requires bruising the picked leaves.

I shook like a leaf, pun intended, when I interviewed for that job. I was nervous and I’m always cold, but beneath the store’s ceiling fans, I slurped down a well-meant iced tea offered by the store’s owner. Later, I’d know that Ruth, the manager, always set the fans to max speed because she got warm quickly. I interviewed in the closet-like back office, which smelled strongly of florals and cinnamon. As my sense of humor thawed out, I told the store’s owner and Ruth that they didn’t need to worry about my extracurricular schedule interfering with my work, because I was “aggressively unathletic” and uninvolved in sports. They laughed hard at this. I described myself as a tea connoisseur to the owner and Ruth, even though I didn’t know the names for the filters, infusers, and decanters stacked high around us.

Working at the tea store, my mental health flourished. Having somewhere to go all my own was a novel experience, having always attended school and most activities with my twin sister. I learned that I needed individuality. I had felt invisible; customer service work, with the nicer-than-normal tea customers, revealed me. I received compliments, made jokes, and met so many types of families, couples, and happy alone people. My boss Ruth was the queen of the store; she knew customers by name and often people came in just to talk to her. She told and repeated her stories—how her sister (one of nine siblings) was named Arletta after a department store worker her mother admired, how her childhood house smelled at Christmas, and how the day she delivered her son, there was a parade outside their house that wouldn’t be diverted.

Ruth was in her early sixties when I met her, and she had wise hazel eyes and glasses, gray curly hair, and always wore sparkly Kohl’s shirts and capris. I remember the way she swayed when she walked, steady like a metronome, and the way her hands spiderwebbed the bottom of the copper tea canisters when she returned them to the shelves. Her favorite animal was the dragonfly, and on her first date with her husband in the 70s, he’d shown up wearing maroon flares and a red polo shirt.

From her, I learned to love my work. Diligent and creative, she talked to customers in a way that was so personal and kind, I felt inferior. I learned how to speak of people gently and to trust my gut; she once stood protectively over my shoulder as a man lingered at my register. She laughed at my childhood idea that I’d marry somebody named Dillon so that together we’d be “Dilemma,” and at my next shift she told me she had quoted the story to her husband. During the busy Christmas season, she’d catch my eye between brews and send me a wink. When my grandma visited me in the store once, Ruth told her that I was the daughter she wished she’d had.

For my birthday, she and another coworker bought a teapot for me. I had proclaimed my love for it often; it was cast iron, comically small in its capacity to hold only eight fluid ounces, and colored a subdued red. I never bought Ruth a personal present like that. Guilt pricks me now as it did then, and when I try to unravel what stopped me, I come up with layers of fear. I doubted I could find a gift so good, and I sidestepped commitment. To buy something for a coworker felt permanent and weighty, and I carried a fear of marking our relationship as special. Ruth was special, and I was aware at the time of how much she meant to me. But I have a knack for compartmentalizing and had long since decided on my group of friends, the only people I bought presents for. I didn’t believe I had the emotional space to start buying presents for a boss. I have OCD, you see, and it mainly affects me through a strong lack of enthusiasm for changing a routine.

I scuffled with my reluctance. In our city, there’s a unique tradition called Hidden Rocks. The idea is to paint rocks, usually with a picture or a kind message, and place them around the city. Finders of these rocks keep them or move them for another person to find, and Ruth loved collecting them. She had a row of them lining her old minivan’s dashboard, and often our shared shifts involved her showing me photos of her latest finds. My school assigned me to paint a rock with something personal to me. I painted my rock teal, overlaid with a hot pink outline of a teacup. I brought it to work with me and slipped it onto the storefront’s window sill because I was too apprehensive to give it to Ruth myself. I have a memory of her picking it up excitedly, but that memory might be fabricated, a work of imagination. I want to believe it’s real, because she deserved something from me.

When she died of pancreatic cancer last year, I struggled with how little I felt I’d done for her. Many of us tea workers attended her funeral. We caught each other’s eyes as we walked in but couldn’t quite look at the casket. We stood still in the asymmetrical pews. From the back of the congregation, we tried to communicate our love to her husband and son, surrounded by people who looked just like her. When we were the last ones left after the casket had been carried out, we hugged. Some of us cried into each other’s shoulders and tried to dry our faces as quickly as we could, and others just stood there, hands empty and fidgety. It was unlike the way we’d always seen each other.

The church was so different from the tea store, which smelled like lavender and vanilla; vaguely leafy. It often had tea splotches on the carpet and usually somebody was laughing. There were clouds of steam and swishing sounds of bags filling. Pens scratching— Ruth had beautiful handwriting and mine had grown much better. Timers beeping.

In the church, the ceilings were high and insistent. I never liked the pews, angled at a slant, or the diamond-tiled floor like a warped checkers game.

I was way off to the side and behind a pillar, hidden, with hot water being poured through my insides.

Emma Strick is a junior English major who is graduating early at Marquette University, where she works and writes for the Marquette University Press. She has earlier publications in non-fiction, and this is her first piece of published creative non-fiction. In her spare time, she enjoys tea drinking, funny people, and general rumination.

Harry Shipler, “National Tea Importing Co., Tea” (J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, 1920): https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s67s9xhx.